Religion and Language Learning: A Case of Language Learning Strategies in the Tanzanian Sociolinguistic Environment

Ben Nyongesa Wekesa

Kibabii University

3.1 Abstract

The study examined religion as a sociocultural determinant of the choice of Language Learning Strategies among learners of English in the Tanzanian context. Basing on Vygotsky’s Sociocultural Theory, the study hypothesized that religion is a significant factor in the choice of language learning strategies. A total of 530 respondents, drawn from both secondary schools and university using the SILL questionnaire, participated. Using SPSS, descriptive mean scores and t-test were computed to establish the existence of statistical significant differences in terms of the overall strategy, the six strategy categories and individual strategy items between Christians and Muslim language learners. The t-test for equality of Means for the overall strategy use between Christian respondents and their Muslim counterparts showed statistical significant differences (t=3.641, df=508, p<.05). The Mean frequency for the Christian respondents in the overall strategy use was 3.458; SD= .680 while that for the Muslim respondents was 3.240; SD =.703. The results, therefore, showed that Christian respondents reported using more strategies than did their Muslim counterparts. With regard to the six strategy categories, the t-test results for equality of Means performed showed that all the six strategy categories were significantly different (Cognitive (t=5.801), metacognitive (t=4.387, social (t=3.609), Affective (t=3.044), Compensation (t=2.542) and Memory (t=2.464) all at df=508). Metacognitive strategy category were highly chosen by both Christian and Muslim (Christianity Mean=4.009, Islam, Mean=3.73). Social strategies were highly used by Christian respondents (Mean=3.720) and moderately used by Muslim respondents (Mean=3.487). All the other strategy categories were of moderately used by both Christian and Muslim respondents. The study therefore recommends that the most preferred strategies (metacognitive and social) should form the core of strategy training. Second, the society in general and all stakeholders should handle the issue of religion with caution since it is a strong determinant in language learning and strategy choice.

Key Words: Language Learning Strategies, Religion, Tanzanian Learning Context, Socio-culture

3.2 Introduction

According to Geertz (1973, pp.90-91), religion is a system of symbols which act to establish powerful, pervasive, and long-lasting moods and motivations in people. Literature on language and religion show that religion is a major force acting on language change as religious facets may bring about not only cultural-linguistic change but may also account for language spread. African societies are commonly depicted as very religious, which is evident in the vast number of Muslim, Christian and other faith groups that exist in most African countries. As Ellis and Ter Haar (2007) rightly puts it: “Religion is an important and pervasive force in the African societies and so religious beliefs operate at every level of society” (p. 68). Religion, like glue, binds societies together. These depictions are relevant in Tanzania as well, which by any account must be described as a country where religion counts and where religious institutions play a very important role in peoples’ lives. According to Leurs et al (2011) faith-based organisations have an increasingly important position in social service provision in Tanzania, including schools.

Religion assumes an important cultural and social position in the Tanzanian society with considerable relevance for everyday activities and social relations. This may have been precipitated by the spread of Christian and Muslim movements that have been termed “fundamentalists” and which are commonly thought to espouse strict prescriptions for both religious practices and social role of religion. Cultural religion refers to the importance of religious practices in the everyday life of believers and by social religion to its importance for social identification and interaction. This study extents the conceptualisation of religion as politics to religion a socio-cultural function in the learning of English in general and the choice of Learning Strategies in particular. There is a broad literature that highlights the persistence of the tendency that religion in Africa is a permeable force in which all aspects of life and society are imbued with spiritual power and meaning (Bompani and Frah-Arp, 2010). Essentially, according to this view, African societies use the lens of religion as a fundamental component of social construction and social interpretation.

In Tanzania, the main religions are Christianity, Islam and traditional religions, often called ATRs (African Traditional Religions). This study excluded ATRs. Though it has been observed that ATRs have considerable influence on political dealings all over Africa (Chabal, 2009), they were excluded in this study because they are non-universal and non-expansionary in nature. This study, therefore, focused on the socio-cultural role of religion played by Christian and Muslim institutions and organisations in Tanzania mainland. Islam has a long history in Tanzania, having set root in the area from the 9th and 10th centuries onwards (Tambila, 2006b, pp. 172-173). Christianity is much younger as the various Christian denominations began their actual missionary work only in the early 19th century, although there had been contacts at a much earlier stage (Tambila and Sivalon, 2006, pp. 225-228). Although there have been tensions between the two faith groups from the very beginning of their encounter in the Tanzanian area, relations between ordinary Muslims and Christian believers have been cordial.

Heilman and Keiser contends that both religious groups may be expected to be relatively equal in terms of strength and numbers (2002, p. 703). Islam in sub-Saharan Africa is commonly seen as distinct from its Middle Eastern counterparts, in that a large part of African Muslims adhere to what is called Sufism. In the case of Tanzania, Abdulaziz and Westerlund (1997) mention that three quarters of the Muslim population can be described as Sufi and in terms of Muslim institutions, the vast majority of congregations and organisations are Sunni, as the Shia groups are mainly limited to Aga Khan Islamites, who are predominantly Asian.

With regard to Christianity, it is commonly believed that the Roman Catholic Church (RCC) and the Evangelistic Churches had a close relationship with the government of Nyerere who was a devout Catholic (Mbogoni, 2005). Through their influence on the government, the Catholics hoped to counter what they perceived to be two largest “undesirable tendencies” in society namely Communism and the influence of Islam (Mbogoni, 2005, pp. 128-130). The Catholic had controlled a large part of the Missionary schools and so the spread of western education in colonial times. The concern that the Christian churches expressed was that Muslims were less tolerant of religious plurality in Tanzania and therefore would seek to establish an Islamic state, if Muslims were to assume power. More realistically the RCC feared losing the opportunity and privileges from the government if Muslims took over.

Throughout the 1960s and most of the 1970s, the mainstream churches were by far the most dominant Christian institutions in Tanzania, while Muslims were represented exclusively by the Chama Cha Mapinduzi (CCM) dominated by the Baraza Kuu la Waislamu Tanzania (BAKWATA). In early 1980s, this started to change, the Pentecostal movement spread with increasing pace in Tanzania, and later various Muslim organisations emerged who challenged the position of BAKWATA. The revivalist groups were frequently confrontational as the Pentecostal groups engaged in crusades which were focused on the conversion of Muslims. The Muslim fundamentalist grouping in turn increasingly engaged in Mihadhara, that is, open-air comparative preaching sessions often including statements that were perceived blasphemous by Christians. The discourse also spread to the newly established newspapers such as Msemakweli and An-Nuur, which thus emerged as religious media outlets (Mbogoni, 2005, pp. 171-180).

The bone of contention being discrimination, Muslims believe that they have been discriminated against for so long in terms of leadership, education and employment since the colonial times. The main issue around education was that Christians have maintained an educational advantage over the Muslims, which harks back to the colonial education system (Ishumi et al, 2006). The basis for these imbalances was laid down during the British colonial rule, as a shift occurred from a dual system of government and private schools to an emphasis on private sectors. It was mainly the missions who could afford the large scale construction of schools, which they undertook with particular intensity while the colonial government put little effort into provision of education. As a result, there was a clear imbalance in the number of Christian and public schools towards the end of colonial rule. This scenario created a negative attitude among the Muslims who see anything associated with colonialists, in this case the English language and western culture, as a reminder of the bitter past since education in colonial Tanganyika was linked to social and economic mobility. The historical distribution of education opportunities is an important key to understanding Muslim complaints, then and now, about their marginalisation.

The validity of these grievances has been the subject of an intensive debate, where the response from some Christian institutions has essentially been that Muslims were themselves to blame for the educational imbalances, since secular education had not been held in high regard in the Muslim community and institutions. This is evident even to date (Heilman and Keiser, 2002, p.702). From religious lens, English is seen as a language of colonialists and a tool for colonialism that threatens the fabrics of African traditions in general and the Islamic religion in particular. It is for this reason that Arabic and Kiswahili are preferred to English among Islamic masses. Such attitudes and value attachments eventually have a ripple effect that spreads to the language classrooms.

According to Al-Shuwairekh (2001) in his study of vocabulary learning strategies among Saudi Arabian language learners of Arabic as a Foreign Language, Muslim students reported greater strategy use in both non-dictionary use for discovering the meanings of new words and expanding lexical knowledge than their non-Muslim counterparts. As for the individual strategy items, only 15 out of 63 varied significantly according to religious identity in which 11 out of 15 items showing significant variation were used significantly more by Muslim students than by non-Muslims. Although this study demonstrates the importance of social factors in strategy use, it is task-based, that is, it only focused on vocabulary learning. It also focused on language learners of Arabic as a Foreign Language.

A study by Liyanage (2004) compared ethnicity/nationality and religion with a view to seeing which one had a greater influence on the use of LLS, indicated that ethnicity and religion jointly predicted the meta-cognitive, cognitive and social affective strategies of ESL learners in Sri Lanka. He also discovered that the religious identity of the learners, rather than their ethnic identity, is important in determining their selection of learning strategies. Liyanage’s study is important to the present research because of the shared ethno-religious approach to the use of LLSs. Unlike earlier studies that looked at respondents as a whole ethnic group of nationals or region (Hispanics, Asians, Chinese and so on), in ethno-religious approach it is assumed that even within a country or continent, the learners’ socialisation and so their language learning will be influenced by their religious backgrounds.

3.3 Theoretical Framework

Vygotsky’s Socio-Cultural Theory

The Socio-Cultural Theory (SCT) provides a very important underpinning background to the roles of LLSs in facilitating second language acquisition. According to Vygotsky, an individual’s cognitive system is a result of social interaction (Vygotsky, 1978). Such interaction is vital for the development of language acquisition both in formal learning contexts and in natural settings. This theory views Second Language Acquisition as a social semiotic construct. It predicts that learning occurs as a result of mentorship and socio-cultural activity. The form-meaning associations that learners make are situational and cultural-based, and the resulting symbols, that is, the knowledge of the L2 mediate conscious thought relating to those situations and cultural phenomena (Lantolf, 1994). The prediction is that the meta-linguistic knowledge will vary in important ways depending on the context of learning and that learners’ knowledge of various levels of linguistic representation (sociolinguistic, phonological, lexical and strategy knowledge) will vary widely from one learning context to another because each context is defined by a unique set of situations and culture (Lantolf and Appel, 1994). A similar argument taken by the present study is that the choice of LLS is determined by socio-cultural factors.

Internalisation, the zone of proximal development and mediation constitute the core concepts or tenets of SCT (Lantolf, 2000, p.1). Vygotsky maintained that higher psychological functions originate in interaction between individuals (inter-psychological level) before they are transferred within the individual (intra-psychological level). The central concept for SCT is the mediation of human behaviour with tools and signs systems. A tool could be as simple as a textbook or visual materials (Donato and McCormick, 1994), or symbolic language (Kozulin, 1990). Such tools allow us to regulate our environment (Lantolf, 1994, p.418). External social speech is internalised through mediation (Vygotsky, 1978). In this way, SCT link society to the mind through mediation. Language as a tool of the mind bridges the individual understanding of us and particular contexts and situations within the world. Donato and McCormick (1994) also state “social processes and mental processes can be understood only if we understand the tools and signs that mediate them”. LLSs are one such mediation tools in language learning.

Based on his theory of the Zone of Proximal Development, a learner will be able to perform at a level beyond the limit of his or her potential with the scaffolding of a teacher or a more capable peer (Vygotsky, 1978). With such scaffolding and assistance, the learner then gradually becomes more independent in his/her learning. As the learner becomes increasingly equipped with what it takes to be an independent and autonomous learner, the scaffolding should be gradually removed. The scaffolding provided by the teacher in the learning process encompasses all kinds of support to facilitate and enhance learning. LLSs are precisely a kind of scaffolding that teachers can provide. In other words, teachers can teach students new strategies and can help them sharpen their existing ones. Equipped with LLSs through instruction, learners will be able to employ them on their own to continue with their learning process even with the absence of the teacher’s support, after all, teachers will not be there for learners after they leave the learning environment. With the gain of “self-control and autonomy through strategy use” (Oxford and Nyikos, 1989), learners will be able to continue their journey in the learning of either a second or a foreign language. In a classroom situation, Donato and McCormick (1994) say that collaborative work among language learners provides some opportunity for scaffolded help as in expert-novice relationships in the everyday setting.

Socio-cultural linguists see language acquisition in social terms. For them, L2 learning is a matter of problem solving in a master-apprentice relationship. Language learning means joining a second culture and is seen as a process of group socialisation, where language is a tool for teaching group traits, values, and beliefs. Language learning becomes difficult where learner’s cultural values and beliefs and practices conflict with those of the second culture. Alegre (2001) says that the more a classroom reflects the actual culture of the target language, the more students would increase not only their communication skills, but also their ability to transcend culture by internalising the tools and symbols that define that culture. The position taken in this study that language is a social phenomenon and therefore, language learning is influenced by socio-cultural factors is in line with Vygotsky’s rationale for Mediation, the Zone of Proximal Development and Scaffolding since enhancing learners’ potential beyond their mental level is at the heart of the concept of language learning strategies.

3.4 Methodology

This study was carried out in Tanzania mainland. Tanzania mainland was chosen as the study site because of its religious plurality. It is not dominated by the Islamic religious group as it is the case of Zanzibar. The targeted population of this research was secondary school learners and university learners of English in Tanzania mainland. Language learners at secondary school and university levels were involved because, first, they have had formal instruction in English for a period of at least seven years. Second, because they are believed to be aware of their own learning strategies and they are also in a position to discuss these strategies. A total of 510 respondents were involved. Such a large sample size was appropriate since the study set to establish statistical significance. According to Dornyei (2007, p.100), the larger the sample size, the higher the chances of reaching a statistical significance.The SILL (Strategy Inventory for Language Learning) questionnaire based on Oxford’s (1990) categorization was used. A Kiswahili version of the SILL was used. This version was important in the Tanzanian context because, first, answering a 50 item questionnaire in English would be time-consuming and difficult to understand for respondents whose LI was not English. So, a translated version would put the learners at ease and also eliminate possible ambiguities. After data collection, each questionnaire was examined individually and coded for statistical analysis using SPSS version 20. First, the researcher conducted descriptive statistics, including percentages, means and standard deviations to summarise the learners’ responses to strategy preference. Secondly, independent t–tests were conducted. The t-test tested the hypotheses of equality of means of Christian and of Muslim language learners. To determine the statistical significance throughout the study, significance levels of p?.05 was used.

3.5 Results

The study was guided by three objectives, that is, a) to establish the overall strategy use in relation to the learners’ religion, b) to find out how the six strategy categories varied with religion and, c) to establish how individual strategy items varied with the learners’ religion. Oxford’s (1990) key for the classification of the strategy frequency scale was adopted. In it, high use ranges from 3.5-4.4 (usually used) and 4.5-5.0 (almost always or always used), medium use ranges from 2.5-3.4 (sometimes used) while low use ranges from 1.0-1.4 (never or almost never used) 1.5-2.4 (usually not used). The following were the results:

The Overall Strategy Use in relation to the learners’ religion

Table 1 below shows the overall strategy use.

Table 1 Overall Strategy Use in relation to the respondents’ religion

Religion N Mean SD t df

Christianity 255 3.458 .680 3.641 508

Islam 255 3.24 .703

The results in Table 1 above showed that the t-test for equality of Means for the overall strategy use between Christian respondents and their Muslim counterparts showed statistical significant differences (t=3.641, df=508, p<.05). The Mean frequency for the Christian respondents in the overall strategy use was 3.458; SD= .680 while the Mean of frequency for the Muslim respondents was 3.240; SD =.703. The results, therefore, showed that Christian respondents reported using the strategies more than did their Muslim counterparts.

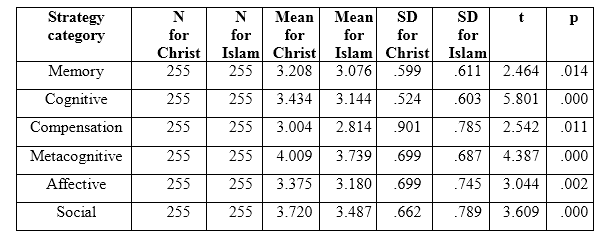

Religion and the Six Strategy Category

Table 2 below presents the results of the six strategy categories and religion.

The t-test results for equality of Means performed to find out if there were any significant differences between the strategy categories and religion showed that all the six strategy categories were significantly different. Cognitive (t=5.801, df=508), metacognitive (t=4.387, df=508) and social strategy category (t=3.609, df=508) showed statistical differences on the religion variable. Metacognitive strategy category were used by both Christian and Muslim respondents at a high frequency (Christianity Mean=4.009, Islam, Mean=3.73) while social strategies were used at a high frequency by Christian respondents (Mean=3.720) and medium frequency by Muslim respondents (Mean=3.487). All the other strategy categories were of medium use frequency by both Christian and Muslim respondents. The results also showed that the Christian respondents used all the six strategy categories more often than their Muslim counterparts.

Religion and Use of individual strategies

Table 3 Learning strategies which were found to be statistically different on the religion variable

| Item No. | Strategy item | Religious affiliation | Mean | Std. Dev. | Std. Error Mean | t | Sig. 2-tailed |

| 1 | I think of relationships between what I already know and new things I am learning in English (MEM) | Christian | 3.46 | 1.096 | .069 | 2.647 | .005 |

| Islam | 3.22 | .974 | .061 | ||||

| 2 | I use new English words in a sentence so I can remember (MEM) | Christian | 3.42 | 1.101 | .069 | 2.184 | .025 |

| Islam | 3.20 | 1.168 | .073 | ||||

| 3 | I connect the sound of a new English word (MEM) | Christian | 3.33 | 1.233 | .077 | .071 | .005 |

| Islam | 3.32 | 1.251 | .078 | ||||

| 4 | I remember a new English word by making a mental picture (MEM) | Christian | 3.46 | 1.315 | .082 | 3.228 | .000 |

| Islam | 3.08 | 1.372 | .086 | ||||

| 9 | I remember new English words or phrase (MEM) | Christian | 3.22 | 1.322 | .083 | 2.201 | .025 |

| Islam | 2.96 | 1.293 | .081 | ||||

| 14 | I try to start conversations in English (COG) | Christian | 3.27 | 1.119 | .070 | 2.574 | .01 |

| Islam | 3.00 | 1.186 | .074 | ||||

| 15 | I watch TV shows spoken in English (COG) | Christian | 3.67 | 1.246 | .078 | 4.448 | .000 |

| Islam | 3.16 | 1.360 | .085 | ||||

| 16 | I read for pleasure in English (COG) | Christian | 2.98 | 1.250 | .078 | 3.709 | .000 |

| Islam | 2.56 | 1.281 | .080 | ||||

| 17 | I write notes, messages, letters, or reports in English (COG) | Christian | 3.74 | 1.114 | .070 | 7.333 | .000 |

| Islam | 2.98 | 1.226 | .077 | ||||

| 18 | I first skim an English passage (read over the passage (COG) | Christian | 3.47 | 1.206 | .076 | 3.432 | .000 |

| Islam | 3.08 | 1.345 | .084 | ||||

| 19 | I look for words in my own language that are similar (COG) | Christian | 3.19 | 1.291 | .081 | 2.837 | .005 |

| Islam | 2.87 | 1.269 | .079 | ||||

| 20 | I try to find patterns in English. (COG) | Christian | 3.40 | 1.182 | .074 | .368 | .035 |

| Islam | 3.36 | 1.227 | .077 | ||||

| 22 | I try not to translate word-for-word (COG) | Christian | 3.09 | 1.367 | .086 | 3.308 | .000 |

| Islam | 2.70 | 1.282 | .080 | ||||

| 23 | I make summaries of information that I hear or read (COG) | Christian | 3.39 | 1.231 | .077 | 4.341 | .000 |

| Islam | 2.91 | 1.278 | .080 | ||||

| 25 | When I can’t think of a word during a conversation (COMP) | Christian | 3.09 | 1.377 | .086 | 2.179 | .03 |

| Islam | 2.83 | 1.345 | .084 | ||||

| 26 | I make up new words if I do not know the right ones (COMP) | Christian | 2.83 | 1.384 | .087 | 2.625 | .005 |

| Islam | 2.51 | 1.383 | .087 | ||||

| 27 | I read English without looking up every new word (COMP) | Christian | 2.67 | 1.323 | .083 | 2.164 | .03 |

| Islam | 2.42 | 1.255 | .079 | ||||

| 29 | If I can’t think of an English word, I use a word in L1(COMP) | Christian | 3.59 | 1.220 | .076 | 2.163 | .03 |

| Islam | 3.34 | 1.356 | .085 | ||||

| 30 | I try to find as many ways as I can to use my English(METCOG | Christian | 4.05 | 1.032 | .065 | 2.710 | .005 |

| Islam | 3.79 | 1.155 | .072 | ||||

| 31 | I notice my English mistakes and use that information (METCOG) | Christian | 3.79 | 1.243 | .078 | 3.669 | .000 |

| Islam | 3.38 | 1.243 | .078 | ||||

| 32 | I pay attention when someone is speaking English (METCOG) | Christian | 4.34 | .849 | .053 | 2.552 | .01 |

| Islam | 4.13 | .986 | .062 | ||||

| 33 | I try to find out how to be a better learner of English (METCOG | Christian | 4.27 | 1.076 | .067 | 2.903 | .000 |

| Islam | 4.00 | 1.029 | .064 | ||||

| 34 | I plan my schedule so I will have enough time (METCOG) | Christian | 3.73 | 2.165 | .136 | 2.028 | .04 |

| Islam | 3.41 | 1.190 | .075 | ||||

| 35 | I look for people I can talk to in English (METCOG) | Christian | 3.75 | 1.150 | .072 | 3.546 | .000 |

| Islam | 3.37 | 1.269 | .079 | ||||

| 36 | I look for opportunities to read as much as possible (METCOG) | Christian | 3.89 | 1.065 | .067 | 2.534 | .01 |

| Islam | 3.65 | 1.101 | .069 | ||||

| 37 | I have clear goals for improving my English skills (METCOG) | Christian | 4.09 | .968 | .061 | 2.291 | .02 |

| Islam | 3.89 | 1.003 | .063 | ||||

| 39 | I try to relax whenever I feel afraid of using English (AFF) | Christian | 3.15 | 1.397 | .087 | 2.199 | .025 |

| Islam | 2.89 | 1.258 | .079 | ||||

| 40 | I encourage myself to speak English even when I am tensed(AFF) | Christian | 4.09 | 1.053 | .066 | 2.424 | .015 |

| Islam | 3.86 | 1.102 | .069 | ||||

| 42 | I notice if I am tense or nervous when I am studying (AFF) | Christian | 3.55 | 1.169 | .073 | 2.356 | .015 |

| Islam | 3.30 | 1.236 | .077 | ||||

| 44 | I talk to someone else about how I feel (AFF) | Christian | 3.21 | 1.261 | .079 | 2.801 | .005 |

| Islam | 2.88 | 1.361 | .085 | ||||

| 46 | I ask English speakers to correct me when I talk (SOC) | Christian | 3.56 | 1.192 | .075 | 2.960 | .000 |

| Islam | 3.22 | 1.375 | .086 | ||||

| 47 | I practice English with other students.(SOC) | Christian | 3.91 | 1.058 | .066 | 2.141 | .003 |

| Islam | 3.70 | 1.173 | .073 | ||||

| 49 | I ask questions in English (SOC) | Christian | 3.64 | 1.088 | .068 | 4.093 | .000 |

| Islam | 3.23 | 1.182 | .074 | ||||

| 50 | I try to learn about the culture of English speakers (SOC) | Christian | 3.34 | 1.266 | .079 | 2.707 | .005 |

| Islam | 3.04 | 1.253 | .078 |

(with equal variance assumed at on p<.05)

(MEM=memory, COG=cognitive, COMP=compensation, METCOG=metacognitive, AFF=affective and SOC=social)

A total of thirty four out of fifty strategy items showed statistical significant differences with religion. It is interesting to note that, among the strategy items which were statistically significant on the religion variable, a total of six items belong to the memory strategies. These were “I watch TV shows spoken in English” strategy Item No 15 (t=4.488, df=508), “I read for pleasure in English” strategy No 16 (t=3.709, df=508), “I write notes, messages, letters, or reports in English” strategy Item No 17 (t=7.333,df=508), “I first skim an English passage before I read over the passage” strategy No 18 (t=3.432, df=508), “I try not to translate word-for-word” strategy Item No 22 (t=3.308, df=508) and “I make summaries of information that I hear or read” strategy Item No 23 (t=4.341, df=508). 2 metacognitive and 2 social strategy items were also significant on the religion variable. These were “I notice my English mistakes and use that information” strategy No. 31 (t=3.669, df=508), “I try to find out how to be a better learner of English” strategy Item No 33 (t=2.903, df=508), “I look for people I can talk to in English” strategy Item No 35 (t=4.093, df=508), “when others make mistakes in speaking, I notice their mistakes and keep myself from making the same ones” strategy Item No 46 (t=2.960, df=508) and “I ask questions in English” strategy Item No 49 (t=4.093, df=508). Only 1 memory strategy item “I remember a new English word by making a mental picture” Item No 4 (t=3.028, df=508) was highly significant with religion.

Although compensation and affective strategy items showed significant differences, the significance levels were not high. Of importance to note too is the fact that a compensation strategy Item No 27 “I read English without looking up every new word” registered a low frequency use among the Muslim students (M=2.42) while strategy Item No 26 “I make up new words if I do not know the right ones” was just at the medium use cut of point (M=2.51). In all the strategy items that were significant with religion, Christian respondents used more strategies than their Muslim counterparts.

3.5 Discussion and Implications

The overall strategy use was found to be statistically significant between Christian learners and Muslim ones (p=.004). The Mean frequency for Christian learners of English in the overall strategy use was 3.458 while the Mean frequency of Muslim learners was 3.240. This implies that Christians have a positive attitude towards secular education and Western culture whose key agent is the English language. In addition, since language learning is a social activity, Christians, both male and female, interact freely with others, including strangers. This gives them an edge over the Muslims in language learning.

With regard to religion and the six strategy categories, the study showed all the categories were significantly different but at different levels. Cognitive, metacognitive and social strategy categories showed higher significance levels of p=.000. The metacognitive strategy category was used by both Christian and Muslim students at a high frequency (Christianity, Mean=4.009, Islam, Mean=3.73) while social strategies were used at a high frequency by Christian student (Mean=3.720) and medium frequency by Muslim students (Mean=3.487). All the other strategy categories were of medium frequency use by both Christian and Muslim students. This observation that religion is statistically significant with all the strategy categories shows that religion is a strong language learning determent. This can be attributed to the fact that religion plays a key role in value and attitude formation (See Geertz, 1973; Crystal, 1976 and Dornyei, 2005). Christian language learners seem to have a soft-spot for English. English language has been also associated with Western culture which was widely propagated by Christianity. Language spread itself is the carrier of socio-cultural change.

From the results, it emerged that Christians in Tanzania had a positive attitude towards the English language and valued it as the language of their religion. They have embraced televangelism and also watch both religious and secular TV programmes in English which expose them to more authentic use of English. The sermons are also conducted in English in a number of churches. Christian learners, therefore, have more exposure and opportunities to practice English hence are poised to be better English language learners and strategy users. The fact that studying L2 involves studying L2 culture and trying to understand other people (Kramsch, 2000) implies that Christian language learners are likely to learn English faster and more efficiently than their Muslim counterparts. In general, therefore, learners’ attitude towards the target language, which can be shaped by religion, plays a key role in language learning. The positive it is; the faster the language learning is likely to be.

Islam in Tanzania, on the other hand, has helped the spread of Arabic and the Arab socio-cultural values. As noted earlier, there has been a power play between Christian and Islamic institutions and faith. There is evidence of competition and conflict between religious groups in the same way that there is conflict and competition between ethno-linguistic groups. Such competition and conflicts manifest themselves in language learning in general and language learning strategy use in particular since, as Geertz (1973) argues, the moods and motivations will be working in the background. This explains the difference in strategy choice and use between the Christians and Muslims studied in the present study. This observation implies that religion, a socio-cultural factor determines our motivation and moods, and therefore, it should be treated with caution in language learning and teaching.

3.6 Conclusion

Religion shapes the values and attitudes of its followers. This influence, eventually find its way into the language classroom. Religion is, therefore, a strong sociocultural determinant of the choice and use of language learning strategies in particular and language learning in general in the Tanzanian learning context.

References

Abdulaziz, Y. L (2013). Islam and Early Globalization in the Indian Ocean World (An East African Perspective). A paper presented at the International Symposium on the History and Culture of the Islamic Civilization in Eastern Africa, Zanzibar, Tanzania. 2-4 September 2013.

Abdulaziz, Y. L. and Westerlund, D. (1997). African Islam in Tanzania. Accessed15.10.2013, http:/www.islamfortoday.com/Tanzania.html#literature.

Alegre, M.A (2001). Vygotsky and Socio-cultural Theory: Key Concepts and Application in the Language Classroom.

Al-Shuwairekh, A. (2001). Vocabulary Learning Strategies Used by AFL (Arabic as a Foreign Language) Learners in Saudi Arabia. Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation. The University of Leeds. Available: http://www. itransfer.org/IAI/FACT/Forms/IAI Library.

Bompani, J. and Frahm-Arp (2010). (eds.). Development and Politics from Below. Exploring Religious Spaces in the African States. Non-governmental Public Series. Palgrave :Macmillan.

Chabal, P. (2009). Africa: The Politics of Smiling and Suffering. University of KwaZulu-Natal Press, Scottville, South Africa.

Crystal, D. (2003). English as a Global Language. (2nd Ed.) Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Donato, R. & McCormick, D. (1994). A Socio-Cultural Perspective on Language Learning Strategies: The Role of Mediation. The Modern Language Journal 78, pp. 453-464

Dörnyei, Z. (2005). The Psychology of the Language Learner: Individual Differences in Second Language Acquisition. Mahwah New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates

Fishman, J.A., (2006). A Decalogue of Basic Theoretical Perspectives for a Sociology of Language and Religion. In Omoyini, T and Fishman, J. A. Exploration in the Sociology of Language and Religion (eds.), 13-25, New York: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Geertz, C. (1973). Religion as a Cultural System. In M. P. Banton (Ed.), Anthropological Approaches to the Study of Religion. London: Tavistock Publications, (pp. 1-46).

Heilman, B., and Kaiser, P. (2002). “Religion, Identity and Politics in Tanzania”. Third World Quarterly, 23(4): 56-78.

Ishumi, A., Mushi, S.S and Ndumbaro, L. (eds.) (2006). “Access to and Equity in Education in Tanzania”. In Mukandala, R., Yahya-Othman, S., Mushi, S.S., and Ndumbaro, L (Eds) (2006). Justice, Right and Worship: Religion and Politics in Tanzania. Dar es Salaam: REDET, University of Dar es Salaam.

Kozulin, A., (1990). Vygotsky Psychology. A Bibliography of Ideas. New York: Harvester-Wheatshesf.

Kramsch, C. (2000). “Social Discursive Constructions of Self in L2 Learning”. In J.Lantolf (Ed.), Sociocultural Theory and Second Language Learning. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 133-135.

Lantolf, J. P., and Appel, G. (1994) Vygotskian Approaches to Second Language Research, Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

Lantolf, J.P. (Ed.). (2000). Socio-Cultural Theory and Second Language Learning. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lantolf, J.P., (1994). Introduction to the Special Issue. Modern Language Journal. 78, pp. 419-420.

Leurs, R., Tumaini-Mungu, P. and Mvungi, A. (2011). Mapping the Development Activities of Faith-Based Organisations in Tanzania. Religion and Development Research Programme. Working Paper 58, University of Dar es Salaam. Retrieved on 15.6. 2014 from http:/www.dfd.gov.uk/r4d/Output/186254/Default.aspx.

Liyanage, I. J. B. (2004). An Exploration of Language Learning Strategies and Learner Variables of Sri Lankan Learners of English as a Second Language with Special Reference to Their Personality Types. Unpublished Doctorate Thesis, Griffith University.

Liyanage, I.J.B., Grimbeek, P., & Bryer, F. (2010). Relative Cultural Contributions of Religion and Ethnicity to the Language Learning Strategy Choices of ESL Students in Sri Lankan and Japanese High Schools. The Asian EFL Journal, 12(1), pp. 165–180.

Mbogoni, L. (2005). The Cross and the Crescent. Religion and Politics in Tanzania from the 1880s to 1990s. Mkuki na Nyota Publishers, Dar es Salaam.

McGrath, A. E. (2000a). The Future of Christianity. Oxford (UK), Blackwell.

McGrath, A. E. (2000b). English: The Language of Faith. In McGrath, A. E. The Future of Christianity. Pp. 90-98.

Ministry of Education and Culture “Education Circular No 2 of 1998”.

Ministry of Education and Culture, (2005). The English Syllabus for Secondary Schools, Form I-IV. Dar es Salaam. MOEC.

Omoniyi, T. and Fishman, J. A. (2006). Exploration in the Sociology of Language and Religion. New York: John Benjamins Publishing Company

Oxford, R. L & Nyikos M. (1989). Variables Affecting Choice of Language Learning Strategies by University Students, The Modern Language Journal, 73(3): 291-300.

Swilla, I. N., (2009). Languages of Instruction in Tanzania: Contradictions Between Ideology, Policy and Implementation. African Study Monograph, 30 (1): 1-14.

Tambila, K. (2006b) “Intra-Muslim Conflicts in Tanzania”. In Mukandala, R., Yahya-Othman, S., Mushi, S.S., and Ndumbaro, L (Eds) (2006). Justice, Right and Worship: Religion and Politics in Tanzania. Dar es Salaam: REDET, University of Dar es Salaam.

Tambila, K., and Sivalon, J. (2006) “Intra-Denominational Conflicts in Tanzania’s Christian Churches”. In Mukandala, R., Yahya-Othman, S., Mushi, S.S., and Ndumbaro, L (Eds) (2006). Justice, Right and Worship: Religion and Politics in Tanzania. Dar es Salaam: REDET, University of Dar es Salaam.

United Republic of Tanzania (1984). Educational System in Tanzania towards the Year 2000: Recommendations of the 1982 Presidential Commission on Education. Ministry of National Education, Dar es Salaam.

United Republic of Tanzania: Ministry of Education and Culture (1995). Education and Training Policy. Dar es Salaam. MOEC.

Vygotsky, L. (1986). Thought and Language: Newly Revised and Edited by Alex Kozulin. Cambridge, Massachusetts: the MIT Press.

Vygotsky, L.S. (1978) Mind in Society. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.