Linguistic Variations in Spoken Kiswahili: A Case of Form One Students from Bungoma East Sub County

Colleta N. Simiyu

4.1 Abstract

The research paper identified and described phonological, morphological and grammatical variations in Kiswahili spoken by form one students selected from private/boarding primary schools and public day schools. The research then correlated the variations observed with the student’s exposure to the standard Kiswahili. This study made use of the sociolinguistic interview and participant observer technique as methods of data collection and judgemental sampling technique to select a sample size for the study. We came to the conclusion that Swahili spoken by students from local public day schools from Bungoma East Sub County varies from the standard Swahili. This variation cuts across all the social variables investigated.

Key Words: Linguistic variable, Social variable.

4.2 Introduction

Members of different speech communities use styles of speaking that are distinctive, consistent and rule – governed (Nancy Bonvaille 1997). These styles may differ from forms of speech generally held to be standard in their choices of pronunciation, words or grammar but they are nonetheless, “correct” and follow the rules accepted and used by speakers in their neighborhoods and networks. Wardhaugh (1998) points out that spoken forms of a language are not uniform entities but vary according to the area people come from, their social class, their level of education, among other social variables. For instance, the Swahili language as used in Kenya is bound to show variation from the standard Swahili due to differences in sociolinguistic contexts. Because of different contexts, most speakers lose their communicative efficiency leading to a wide variety of outcome in lexical, phonological and morphological patterns. This could be a case of form one students selected from public day schools in Bungoma East sub county which presents us a sociolinguistic area of study in our project.

The language – in – education policy in Kenya is spelled out in the Totally Integrated Quality Education and Training Report, a guideline for the education system in Kenya (Njoroge, 2008).In the rural set- ups, the medium of instruction in the lower primary is the learner’s mother tongue or the dominant language within the school’s catchment area. Within private schools and boarding schools where the population is made up of speakers from different ethnic groups, Kiswahili and English are the medium of instruction. Kiswahili like English plays a significant role in Kenya as the language of education, administration, commerce and modernization (Abdullaziz, 1991).

Much of the available research into the spoken Swahili language in Kenya has concentrated on the word structure and the sentence structure of the language. However, hardly any of these approaches consider how social variable such as education interplay with Swahili to reflect the socio- cultural changes that Swahili has been made to undergo in Kenya. Our research therefore focused on analyzing spoken Swahili language as used by form one students from Bungoma East Sub County. The two social groups investigated include students selected from public day schools and those selected from private schools or boarding schools.

The study sought to achieve the following objectives; a) to describe the phonological and grammatical characteristics of the variety of Swahili spoken by form one students selected from public day schools and private or public boarding schools, b) to determine how the variations depart from the Swahili standard variety.

4.2.1 Social Variable

Sociologists use a number of different scales for classifying people when they attempt to place individuals somewhere within a social system. (Wardhaugh, 1998). An educational scale may divide people into a number of categories as follows: graduate or professional education; college or university degree; attendance at college or university but no degree; high school graduation, some high school education, and less than seven years of formal education (Wardhaugh 1998; 150). According to Milroy and Milory, two very different types of relationships exist on the level of class and of network. Systems of class are based on ‘conflict division and inequality” whereas networks are held together through consensus. In our research, student’s educational background measured by the type of school (public day or private/ boarding) was the independent variable. The type of school was used to represent the level of exposure of form one students to Kiswahili language. Twenty of the observed students had gone through public day schools and twenty had gone through either private or boarding primary schools. The latter had at least eight years of instruction in the Swahili language as compared to the former, most of which had been instructed in their mother up to standard eight.

4.2.2 Linguistic Variable

Wardhaugh (1998 p.147) defines a linguistic variable as an item in the structure of a language, an item that has alternate realization, as one speaker realizes it one way and another a different way, or the same speaker realizes it differently on different occasions. Variation is a characteristic of language: there is more than one way of saying the same thing. Speakers may vary their pronunciation, lexicon, or syntax. Our study therefore limited itself to the analysis of the following linguistic variables:

Phonological: (h) realized as ? and

(ka) realized as (h)

Morphological: (si-), (sa-), (- mo)

Grammatical: The use of words like kutenya, kufa, kuanguka,

Double subjects and the excessive use of si-

Table illustrating linguistic variations between students from public schools and those from private/boarding schools

| STANDARD SWAHILI | PUBLIC | PRIVATE/ BOARDING | VARIATION |

| Hospitali | Osipitali | Hospitali | h, ? |

| Nilienda | Sinilienda | Nilienda | Si-, ? |

| Niliweka | Niliwekamo | Niliweka | -mo, ? |

| Kufeli | Kuanguka/ Kufa | Kufeli | |

| Okota | Tenya | Okota |

4.3 Methodology

4.3.1 Research Design

Research within the language variation paradigm falls within quantitative research design (scheneider, 2004). The variationist paradigm builds upon quantitative methodology to establish relationships between social factors and linguistic factors. Nevertheless, quantification is required to differentiate the least preferred varieties from the most preferred varieties. Our study was therefore designed to investigate the relationship between one independent variable (exposure of learners to Kiswahili) and multiple linguistic dependent variables. The descriptive design adopted in the study provides a systematic, factual and actual description of the nature of linguistic variations.

4.3.2Area of Study

To achieve the objectives of the study, data were collected from form one students selected from local day schools in the rural areas of Mikuva, Sipala, Lukusi and Makemo primary schools and form one students selected from boarding schools and private schools from the urban areas of Webuye and Lugulu. The choice of the sub- County was so because it combines both the rural and urban setting with well distributed population. The diverse setting for primary schools in Bungoma East sub- County provided the required information needed for the study. The performance of language especially of Kiswahili at KCPE level was not encouraging in local public day schools. Lack of exposure of students to the spoken language and to different learning materials was cited as one of the causes.

4.3.3 Target Population

The target population of the study was form one students from Bungoma East Sub County selected from both public day primary schools and private/ boarding primary schools. The research sample was made up of 40 form one students, 20 from public day schools and 20 from boarding/private primary schools. The researcher choose on a smaller sample of 40 basing on what Milroy and Gordon (2003) points that variation studies do not require the statistical analysis of hundreds of speakers” records as variations can emerge even from small samples.

4.3.4 Study Sample and Sampling Technique

Judgemental sampling method and the social network approach guided the researcher in choosing the required study sample (Milroy and Gordon 2003). Milroy and Gordon points out that using a judgment sample is appropriate if one is fairly familiar with the basic characteristics of the population (e.g. the basic socioeconomic and ethnic make- up of the community). Thus, judgment sampling entails identifying in advance the target variables which then presupposes the type of respondents to be studied. The sampling technique was apt to our research since it made sense to select the sample in such a way that there was maximum chance for any relationship to be observed. The social network approach on the other hand, looks at an individual in a speech community as having specified networks of relationships with other individuals whom he or she depends on and who in turn depend on him or her (Njoroge, 2008). We also employed the friend of a friend and a friend beyond a friend technique to enter the field to collect the language data.

4.3.5 Data Collection Techniques

The instruments that deemed suitable for the study were the sociolinguistic interview, and the participant observer technique as explained below;

The Sociolinguistic Interview

The sociolinguistic interview is an interview designed to approximate as closely as possible a casual conversation (Wardhaugh 1998; 172). We grouped questions into topical areas which could be arranged and rearranged to flow fairly into one another. The topics chosen were of interest to the form one students which assisted the researcher to minimize the student’s attention. Most questions were open- ended and interviewees were encouraged to talk on any subject that caught their interest, whether or not it was included in the original interview questionnaire. The sociolinguistic interview allowed the researcher to collect a large amount of speech in a relatively short period of time and also to obtain recordings of high quality in which all participants were easily identified.

Questions Expected during the Interviews are given Below;

1 .Kusikiliza na kuzungumza

- a) Taja maneno matatu kwa kila sauti sifwatazo

/b/ /d/ /g/

- Utunzi

- a) Simulia kisa chochote kilichokustajabisha au kilichokufanya uabike siku yako ya kwanza kwenye shule ya upili.

- Kusikiliza na kuzungumza

- a) Waitwa nani?

- b) Wapenda somo lipi?

- c) Jana ulikuwa wapi?

- Wanafunzi wanafaa kufanya nini ikiwa wamepewa majukumu kulingana na uwezo na akili yao?

- a) Taja hulka za mwanafunzi anayependa masomo

- b) Taja tabia za mwanafunzi asiyependa masomo

- c) Kunao wanafunzi wanaopenda kusoma na wasiopenda kusoma kati yenu?

- Ni nini kitafanyika ikiwa wanafunzi watapewa uwezo wa kufanya chochote wapendacho?

- a) Matokoe ya wanafunzi yataathirika vipi?

- b) Uhusiano wa wanafunzi na walimu utakuwaje?

Participant Observer Technique

The researcher also employed a modified participant observer technique where she became part of the system she was studying, and the analysis was based on data collected from forty students of both types of schools with approximately one third from each school. All chosen students participated because each of the school exhibited a pattern of dense and multiplex ties.

Classroom interactions during Kiswahili lessons were also tape- recorded four times to obtain the language data. Since the aim of the research was to find variations in the spoken Swahili of form one student s and to capture these variations as naturally as possible, the participant observer technique helped to establish a more natural and relaxed environment thus lowering the students inhibitions. The first and second classroom participation therefore helped to take care of the observer’s paradox. Only the third and fourth interactions were tape recorded, coded and analyzed.

4.3.6 Data Analysis

The students’ spoken language data was first transcribed, and then analyzed to identify the variants of each. The researcher relied on her encyclopedic knowledge in translating the sounds and tried to be as close as possible to the original meaning of the words. We also made use of the Kamusi sanifu ya Kiswahili in determining a correct description of the specified variation. The total tokens for each variant were then determined by counting frequency of occurrence of the specific variant in the language data of each teacher, in each of the two students categories (public day or private / boarding) and in the entire language data.

The linguistic data was further analyzed statistically to establish whether there was any correlation between the variation observed and the students’ level of exposure to Kiswahili.

4.4 Results

Data analyses revealed that the Kiswahili spoken by form one students selected from public day schools varied significantly from the standard variety. This was noted both in the phonological variations and morphological variations.

4.4.1 Phonological Variations

A major pronunciation trait of public day school students’ speech is the tendency to replace the voiceless consonants with the voiced consonants in the Kiswahili language. The following examples drawn from the students’ spoken data illustrates the nature of variation. The transcriptions are based on how the students pronounced the specific word.

- (Wakeni) na (wenyechi) walichesa) tensi)

wageni na wenyeji walicheza densi

(The visitors and the villagers danced)

- (Mtomo) wa (chuu) na wa chini (husuia) hewa kwa (kukusana)

mdomo juu huzuia kugusana

(The upper bilabials and lower bilabials prevents the air from interacting)

- (Ukarapati) wa (parapara) (mbofu) unaendelea

Ukarabati barabara mbovu

(Construction of poor roads is in the process)

In the examples 1 2 3 above, the voiceless consonants (k,?,s,t,p) were used in the highlighted words instead of the expected voiced consonants (g,?,z,d,b). For instance, in example (3), the word barabara was articulated in the study as parapara. The use of voiceless consonants instead of voiced consonants is influenced by the fact that Lubukusu (which is the native language of students from Bungoma East Sub County) does not exhibit voiced consonants into its pronunciation.

Phonological variations were also noted in the use of the glottal (h) as shown below;

- Mama amepeleka mtoto (ospitali)

Hospitali

(Mom has taken the child to the hospital)

- Tulinunua (kaawa) kwenye (oteli)

Kahawa hoteli

(We bought cocoa from the hotel)

- Tata yangu anachiandaa kufanya (arusi) mwesi wa tisemba

Harusi

(My sister is preparing for her wedding in December)

In examples 4 5 6 highlighted, there is the omission of the glottal sound (h) in words hospitali, hoteli, kahawa and harusi.

4.4.2 Variation and Change in Morphology

Morphological processes in Swahili language are employed to express grammatical concepts. Some of the most common concepts are person, number, case and such verb categories as tense, aspect and mode. A number of morphological patterns appear in students from public day schools more frequently than students from boarding/ private schools. For instance the occurrence and non- occurrence of the morpheme (si-) in words which do not mark any meaningful class but used for emphasis (as in the preceding list). This prefix though taken as an arrogant way of saying something by teachers and those people who are proficient in Swahili, it is used unconsciously by students as an emphatic marker. It can be attached to any verb by the students to render the speaking style more polite.

Std kiswahii Private/Boarding Public day

I went Nilienda Nielienda Sinilienda

I told you Nilikwambia Nilikwambia Sinilikwambia

I will walk Nitatembea Nitatembea Sinitatembea

Another morphological linguistic evidence of the social variation between students from public day schools and those from boarding / private schools is the distinctive use of the sentence- final particles, that is, morphemes occurring at the ends of sentences that mark speaker attitude or locatives of items. Locative expressions refer to placement of objects, persons and or events in space or time (Nancy 1997; 239). Common particles in students from public day schools indicate locality (-mo) and politeness (-ku) as shown in the conversations below

8 A. Mwalimu: uliweka lini maji kwa mtungi?

(Teacher: When did you place water in the pot?)

Mwanafunzi: (Niliwekamo) jana.

Niliweka

(Student: I placed yesterday)

- Mwalimu: kwa nini hukuweka kwa ndoo?

(Teacher: Why didn’t you store in a bucket?)

Mwanafunzi:Mwalimu hiyo ili (pasukamo) na tena Panya (iliingiamo)

Pasuka ilingia

(Student: Teacher that one is broken and contains a rat)

In example 8A and 8B, the words niliweka, imepasuka and iliingia have been suffixed by the morpheme (-mo). Though the words indicate an action of putting in, the students still add (-mo) to show locality. Apart from (-mo), the suffix (–ko) is also prefixed on words to show politeness as shown below;

- (Nisaidieko) na hiyo kalamu.

Nasaidie

(Assist me with that pen)

In a number of instances especially during story telling time, there was the occurrence of the morpheme (kha-) to show diminutive. The diminutive affix (kha-) is used to describe the size of animals, plants or human beings instead of the standard Kiswahili diminutive affix (ka-). For instance;

10 A. (Khale) (khatoto) (khalikimbia) mbio

Kale kajitoto kalimbia mbio

(That child ran)

- Nisaitie (khachiti) khatoko

Nisaidie Khakijiti O

(Assist me with a small stick)

4.4.3 Choice of Vocabulary

Certain words or categories of words appear with greater frequency in the speech of students from public day schools than those from boarding or private schools. For instance, students from public day schools use words such as ‘kutenya kuni (collecting fire wood), kufa/kuanguka (To fail), instead of using the standard forms of the words kuokota kuni and kufeli. For example,

11 A.student 1: Tupa mpira

(Through the ball)

Student 2: Hapana, wacha huyu atokemo, yeye amekufa/ameanguka.

(No, let this get out of the game, she has died)

Failed

B.Chana tulienda mstuni kutenya kuni na tata yangu.

(Yesterday we went to the forest to collect firewood with my sister)

The use of such words function to signal student’s uncertainty about the validity of their statements where they create an impression of lack of clarity.

4.4.4 Statistical Presentation

The frequency of occurrence of the linguistic variants was calculated and results presented in tables as shown below;

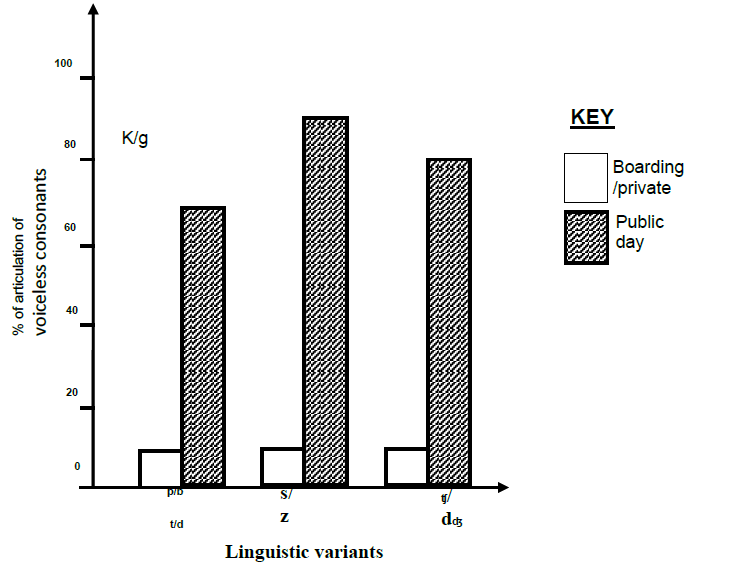

Figure 1: level of exposure to Kiswahili and the articulation of voiceless consonants

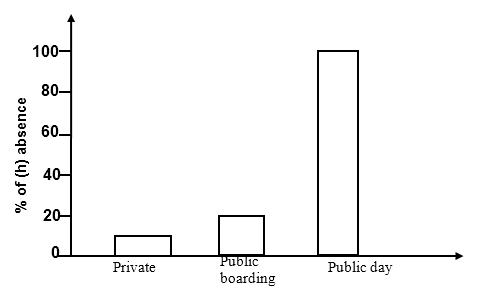

Figure 2: level of exposure to Kiswahili and the percentage of (h) absence in words

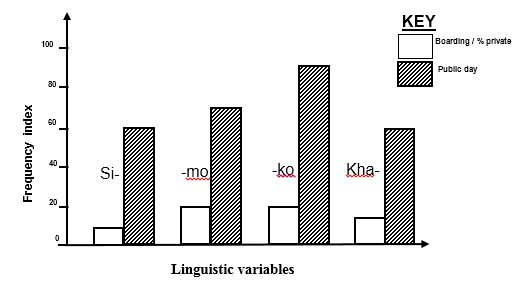

Figure 3: level of exposure to Kiswahili and the use of morphological patterns (si-), (-om) (-ko) and (kha-)

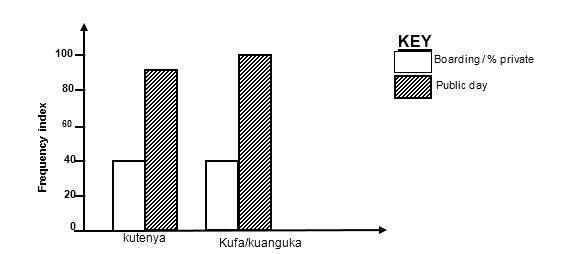

Figure 4: level of exposure to Kiswahili and the use of lexical words kutenya, kufa/kuanguka

As illustrated by the sampled graphs, the spoken Kiswahili of form one students selected from boarding/private schools had fewer variations from the standard Swahili forms as compared to students selected from public day schools. This pattern cut across all the linguistic variants

Table 1 shows the incidence of voiceless consonant use that we found among students selected both from boarding/private schools and public day schools. The table shows that a higher number of students (70%, 90%, and 60%) who were approached used the voiceless stops in place of voiced stops in all possible instances but few (10% and 5%) did so from private/boarding schools.

Table 2: shows that the more exposure of a learner to Kiswahili language for many years, the more likely a learner uses the glottal sound /h/ in words like hoteli (hotel) harusi (wedding), kahawa (coffee) and so on, rather than the corresponding /?/ variant. Form 1 students from public day schools for instance say ‘oteli, ospitali, and kaawa, when they are asked to read a word list containing words beginning in (h-) on majority of occasions. In the use of (h) absence, there is gradient stratification. According to Wolfram and Fasold (1974), gradient stratification is a regular step – like progression in means which matches social groupings.

Table 3 and 4 illustrates the use of morphological patterns and the choice of lexical items. The data suggest that, so far as the morphological patterns (si-, -mo, -ko and kha-) and the choice of lexical items kutenya (to collect firewood) and kufa/kuanguka ( to die or fall down) are concerned, their variant use are related to the background of exposure to Swahili as a language.

4.5 Conclusion

The general finding in this paper is that the Swahili spoken by students from local public day schools from Bungoma East Sub County varies from the standard Swahili. This variation cuts across all the social variables investigated. Of the social variables, mother tongue (Lubukusu) was found to impact heavily on both the phonological, morphological and lexical systems in the spoken Swahili of sampled students used.

Mode of teaching and the level of exposure to the language were also found to influence the variations. In all our linguistic categories observed, the spoken Kiswahili of students from private schools and public boarding schools had fewer variations. This implies that more exposure to spoken Swahili makes students from boarding /private schools to use more target – like Swahili forms than their counterparts who have not had the same level of exposure to the language.

4.6 Recommendation

It is my recommendation therefore, that learners from public day schools will be exposed to the use of standard Kiswahili at an early stage in their education. Though the language in education policy in Kenya spells out that learners from rural set-ups in the lower primary should be instructed in their mother tongue or the dominant language within the school’s catchment area, teachers teaching these schools should be encouraged to expose their learners too to materials written in Kiswahili and also use Kiswahili as a medium of instruction. This will enhance the phonology and grammar of the learners hence making their spoken Kiswahili more intelligible.

References

Bailey, C.J N. (1973) Variation and Linguistic theory. Washington, DC: Center for Applied Linguistics.

Bonvillain, N., (1997) Language, Culture and Communication: The meaning of messages. Library of congress cataloging.

Cheshire, J. (1982). Variation in English dialect: A sociolinguistic study. Cambridge: Cambridge University press.

Labov W. (1966). The social stratification of English in New York City, Washington, D.C, Center for Applied Linguistics.

Milroy, L. & Gordon, M. (2003). Social Linguistics: Method and interpretation, Oxford: Black well.

Njoroge, C.M. (2008). Variations in spoken English used by teachers in Kenya: Pedagogical Implications: Working papers in Educational Linguistics. 23, (2), 73-10.

Schneidera E. (2004). Investigating Variation and Change in Written Documents. In J. Chambers, P. Trudgill & N. Schilling- Estes (Eds.).The handbook of language variation and change (app 67-96).Oxford Blackwell.

Wardhaugh, R. (1989). An Introduction to Sociolinguistics. (2nd Ed). Oxford. Black well.

Weinreich, U., Labov, W. & Herzog, M.J. (1968). Empirical foundations for a theory of language change. In Lehmann, W.P. & Yakov, m. (eds) Directions for historical linguistics: A symposium. Austin; University of Austin press. 95-195.

Wolfram, W. (1993). Identifying and Interpreting Variable. In Preston. D.R. (ed), American dialect research. Philadelphia/ Amsterdam: John Benjamin’s 193-22 1.

![]()

Download: Linguistic Variations in Spoken Kiswahili: A Case of Form One Students from Bungoma East Sub County